Myths are often regarded as simple falsehoods, as being about people or gods that have never existed or events that never happened. But regardless of their historicity, the important part about myths is the fundamental truths that they convey to a community, then and even now. This is especially true for biblical myths, including stories about Jesus. Our American community is still largely Judeo-Christian, and even if one is not Christian or Jewish, all of us still grow up in our largely Judeo-Christian culture and are influenced by it, whether we are fully aware of this or not. Therefore, it behooves us to consider how the teachings and deeds of Jesus (i.e., the truths in the stories) should apply to the important issues that our American community faces today, and what solutions they imply. What would Jesus say about them? What actions would he take? How would he vote?

Background from the Prophets of Israel

What Jesus taught did not spring simply from his own imagination; it was the product of longstanding Israelite tradition, drawing especially upon the prophets in the early to mid- first millennium BCE. At that time, too many Israelites observed empty ritual and prayer and paid lip service to doctrine on the one hand, but actually behaved otherwise, contrary to God’s demands and expectations. The prophet Isaiah, for one, took issue with these folks (1:11, 15-16):

What to me is the multitude of your sacrifices?

says the Lord.

I have had enough of your burnt offerings of rams

and the fat of fed beasts . . . .

When you stretch out your hands,

I will hide my eyes from you;

Even though you make many prayers,

I will not listen;

your hands are full of blood.

Wash yourselves, make yourselves clean;

remove the evil of your doings

from before my eyes;

cease to do evil;

learn to do good;

seek justice;

rescue the oppressed;

defend the orphan;

plead for the widow.

The prophet Amos demanded the same (5:12, 23-24):

For I know how many are your transgressions,

and how great are your sins —

You who afflict the righteous, who take a bribe

and push away the needy in the gate. . . .

Take away from me the noise of your songs;

I will not listen to the melody of your harps.

But let justice roll down like waters,

And righteousness like an ever-flowing stream.

The book of Leviticus, written later, contains rules in line with what these prophets wanted (e.g., 19:11-17). Leviticus 19:10 says to leave some grapes from one’s vineyard for the poor and for the alien. And Leviticus 19:18 introduces a fundamental command, to love one’s neighbor as thyself, which Jesus famously taught (see below).

The import of these moral and ethical commands is that what a person actually does to make the world better is what is most important in order for him or her to be in the right relationship with God, not what one merely says; not just offering thoughts and prayers; and not just performing or attending religious rituals (in today’s world, such as just going to church on Sundays). You have to walk the walk.

What Jesus Taught and Did During His Life

Jesus saw himself as a prophet in the line of the above tradition of teachings. When a Pharisee lawyer asked Jesus what are the most important of God’s commandments in the Law, he replied that they are, first, to love God with all one’s heart, and second (which Jesus said is “like” the first), is to love thy neighbor as thyself (Matthew 22:36-39; likewise Mark 12:28-34; Luke 10:25-28; see also Gospel of Thomas, saying 25). In other words, loving God entails loving one’s neighbor, and vice versa. “On these two commandments hang all the law and the prophets,” Jesus stressed (Matthew 22:40).

This principle finds expression in the more specific teachings of Jesus, as well as in his acts.

His Teachings

A threshold question that a lawyer asked Jesus was, “Who is my neighbor”? Jesus replied by telling the story of the good Samaritan (Luke 10:29-37). (Samaritans were not Jews, but were a related ethnic group generally located in Samaria (the highlands of what is currently the West Bank of the Jordan); their religion differed somewhat from the Jews so they were not considered part of the House of Israel, were deemed ritually unclean, and thus were viewed as foreigners (gentiles). See, e.g., Luke 17:18.) In the story, a man traveling from Jerusalem to Jericho was robbed and badly beaten by robbers, who left him on the roadside to die. A Jewish priest and then a Levite passed by but ignored him, but then a Samaritan arrived, cared for him, and saved him. Jesus asked the lawyer which of the three was a neighbor to the victim. “The one who showed him mercy,” the lawyer replied. And Jesus instructed, “Go and do likewise.” Thus, the “neighbors” whom one should love are not restricted to those who share one’s religion or ethnicity. Jesus himself extended his ministry to foreigners (see below), and he declared that the worthy people of all nations would be gathered together in the Kingdom of God (Matthew 25:32).

Jesus taught that the Kingdom of God would be made up of those who loved God and their neighbors, like sheep who were separate from the goats. He taught that the Son of Man will explain to them, “I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you welcomed me. I was naked and you gave me clothing, I was sick and you took care of me, I was in prison and you visited me” (Matthew 25:35-36). Since the righteous listeners had never met the Son of Man, they asked how they could have performed these kind acts for him. He replied, “Truly I tell you, just as you did it to one of the least of these who are members of my family, you did it to me” (Matthew 25:37-40). Loving one’s neighbor is to love God.

In his Sermon on the Mount, Jesus taught much the same:

Blessed are the meek,

for they shall inherit the earth;

Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness,

for they will be filled.

Blessed are the merciful,

for they will receive mercy.

Blessed are the pure in heart,

for they will see God.

Blessed are the peacemakers,

for they will be called the children of God.

Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness’s sake,

for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

(Matthew 5:5-10)

His Actions

Jesus’s actions exemplified how God wanted people to conduct themselves and love one another. These deeds included:

- Feeding the needy (Matthew 14:15-21; 15:32-39; Mark 6:35-44; 8:1-10; Luke 9:12-17; John 6:4-13)

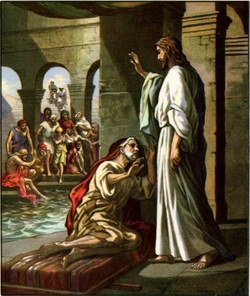

- Healing the sick, and not shunning them (e.g., Mark 7:31-37)

- Throughout the canonical gospels, treating women as equals, and accepting them as his close followers; they played key roles in his ministry, and at his crucifixion and resurrection. See also the Gospel of Mary, in which Mary Magdalene teaches the disciples, since Jesus had recognized her as worthy, while the Gospel of Philip says that Jesus loved Mary Magdalene most of all, because she saw the light better than did the disciples.

- Not shunning but being kind to people whom most of society abhors (tax collectors, prostitutes, lepers, etc.)

- Paying special attention to widows (Mark 12:41-44; Luke 21:1-4), and condemning people who mistreat them (Mark 12:40; Luke 20:47)

- Paying special attention to children, and teaching that they are exemplary and to be emulated (Matthew 18:3; 19:13-14; Mark 7:27; 9:33-37; 10:13-16; Luke 18-15-16)

Jesus also was kind to and performed beneficial deeds for foreigners. In John 4:7-26, he welcomed and taught a Samaritan woman at Jacob’s well, and revealed his messiahship to her (meaning that he could be the messiah for non-Jews too). He traveled to the region of Tyre and Sidon where he healed the daughter of a Phoenician (gentile) woman (Matthew 15:21-28; Mark 7:24-30). In Galilee, he received and taught “great numbers” of foreigners from Tyre, Sidon, and Idumea, from beyond the Jordan (Mark 3:8; Luke 6:17). In Matthew 8:5-13, a Roman centurion appealed to him to heal his servant, and Jesus did so, remarking, “in no one in Israel have I found such faith. I tell you, many will come from east and west and will eat with Abraham and Isaac and Jacob in the kingdom of heaven, while the heirs of the kingdom [of Israel] will be thrown into the outer darkness, where there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth.” So he placed foreigners of good will above unrighteous Jews. According to the Gospel of Philip, Jesus redeemed aliens and made strangers his own.

Like the above-mentioned Israelite prophets, Jesus scolded religious and political leaders who enjoy high positions and luxury, yet do nothing to help the plight of the needy and even prey on them (e.g., Matthew 23:1-12; Mark 12:38-40; Luke 11:42-52; 20:46).

What Would Jesus Say and Do Today?

In light of Jesus’s teachings and deeds, it is easy to see that he would be especially attentive to addressing similar issues that we face today, in the compassionate spirit in which he addressed them during his life, including:

- Caring for the poor, orphans, and widows

- Providing access to health care (including for mental health) regardless of income or wealth; ensuring food quality and product safety

- Ensuring equality for women and protecting their rights

- Combating racism

- Protecting civil rights and human rights

- Ensuring access to justice in our legal system

- Ensuring religious toleration (Christian exclusivity and intolerance (and Christianity itself) arose after Jesus)

- Respecting and valuing diversity

- Providing access to affordable education, so that all people can have better lives

- Ensuring fair treatment of immigrants (whether legal or not, and especially asylum seekers) and other foreigners

- Protecting our environment

Like in Jesus’s time, too often those in power (including some religious leaders) ignore these issues, while too many in our population (including many Evangelicals) nevertheless vote such individuals into public office; such candidates campaign on platforms that are opposed to the above values. And Jesus surely would not support the “prosperity gospel.”

How Would Jesus Vote?

Jesus’s truths and teachings are timeless, and indeed much the same principles are taught in the world’s other religions and spiritual traditions. We must not lose sight of them in both our individual and national lives. Although Jesus did not get into politics, his teachings have obvious applications in our businesses, other institutions, politics, lawmaking, and the justice system. Many other (even more secular) countries are implementing these teachings and values in their national life better than we do here in America. Both Christian and non-Christian Americans should examine who among our existing and aspiring leaders are really embracing and acting in accord with Jesus’s teachings (and similar teachings in other religious and spiritual traditions), hold them to account, and vote accordingly when we go to the ballot box. And we should be activists in furthering these goals, as Jesus was.